Amherst Regional High School

I grew up in the progressive town of Amherst, Massachusetts. To give you an idea of the political temperature: my mother divorced my father in 1995 and became a lesbian, and no one made fun of me for it.

Yes, my mother's wife would pick me up from school (adopted greyhound in tow), and zero jokes were made.

When I was in high school, a wave of outrage about Latin-American stereotypes led to the last-minute cancellation of the senior performance of West Side Story. You know what play the community had no issue with? The Vagina Monologues.

When I was 15, I asked the editor-in-chief of the school paper to bring me on as a columnist. He refused, but encouraged me to start my own thing.

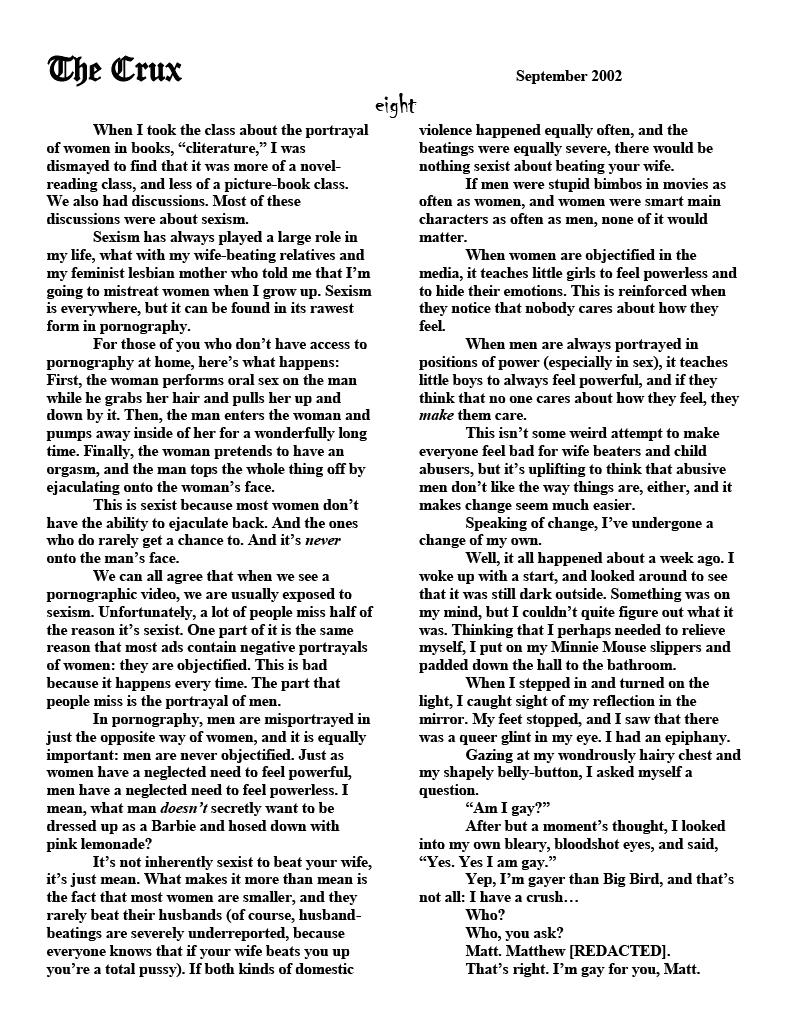

I took his advice and, in 2001, I began self-publishing a single-page newsletter called The Crux. That first year, I wrote about teen dating and social castes (the “Divines” and the “Clammies”), I critiqued my health teacher’s anti-porn messaging, and I slammed an anti-racist Asian culture assembly I was forced to attend, writing, “If Asian women really don't like sex, then how come there're so many Asians?”

I wanted the newsletter to be anonymous, as I’m a shy person, so I clandestinely placed my papers next to other student publications and newsletters. The school staff threw them in the trash. It seems banal and insignificant, but this was my first encounter with government censorship: if there's a designated shelf or bulletin board for student media, public school employees can't just throw some of it out because they don't like what it says.

I found some courage and started distributing The Crux in the lunchroom, walking from table to table and handing out 500 copies per issue. The lunchroom staff (along with some angry teachers) still snapped up any unattended copies, but their efforts to shut down my paper were otherwise thwarted.

That is, until I released issue #5, which earned me a weeklong suspension.

The charge? Sexual harassment and racism. According to the school administrators, I had sexually harassed our recently-resigned principal by making fun of him for being a self-admitted child molester.

You can learn more about him and his 28 accusers here, but the short version is that he goes from community to community molesting boys and facing few repercussions, and has been doing so for 50 years.

A freshman at my high school alleged that Mr. Myers had invited him over to hang out in his hot tub, and Mr. Myers resigned under pressure from the school board. There was an outpouring of support from both students and staff (but not from me) demanding that Mr. Myers be allowed to keep his job.

The Santa Cruz Police Department, whom Myers had been investigated by, caught wind of the allegation and sent a report containing his admissions of molestation to our local paper, The Daily Hampshire Gazette.

I was angry. In my newsletter I bitterly mocked Myers, the school administrators, and the two students who’d naively led a crusade to get him reinstated. I wrote, “My response to Mr. Myers’ controversial hobby of molesting children? I’m going to break up with him, and had I known he was a child molester, I never would have gone out with him in the first place.”

Yes—according to the superintendent (whom I’d also criticized by name), this was me sexually harassing our disgraced child molester ex-principal.

The other justification for the suspension was racism. Reading issue #5 now, I’m surprised at my own white guilt and how much I was still toeing the progressive line. But to the administrators, making fun of the school’s handling of race was the same as being racist. Of course, a state school can’t legally suspend a student for merely having or expressing racist beliefs anyway.

The dean of students, a (very) light-skinned black woman, called me into her office and said, “You don’t know anything about racism because you’re white.”

While he was suspending me, one of the acting co-principals (filling the recently-vacated position) smugly asked me what my black friends thought of my newsletter. I replied, “I don’t have any black friends,” and stared at him, challenging him to reconsider whether my all-white friend group was in spite of or because of the school’s relentless diversity programming.

A Puerto Rican guidance counselor called my father to warn him that she’d overheard some students discussing, in Spanish, following me home and killing me. She explained to them that my piece was satirical and not meant as an insult to Latinos, which they accepted.

(I was still terrified, and as a result I lost the ability to pee in public urinals—permanently. I can stand there just fine, but for the life of me, nothing will come out.)

The editor-in-chief of the school paper, who by now recognized that he’d dodged a bullet by refusing to give me a column, contacted the ACLU on my behalf. A lawyer named Bill Newman wrote the school a letter warning them that they were infringing on my First Amendment rights and urging them to back down.

They did. My suspension was retroactively overturned and I continued to publish The Crux without incident.

That is, until issue #8, in which I professed my gay love for my friend Matt. I invited him to roleplay as Mr. Myers and a helpless boy, or the acting principle and his wife.

Paradoxically, my joking declaration of love came after some sincere reflections about sexism in pornography, right around the time when teens first gained access to hardcore porn.

I was suspended again, this time for obscenity. (The acting co-principals naively assumed my parents wanted to rein me in and invited them to the meeting. My father called Mr. Wehrli a “fucking Nazi” and refused to leave until he called the police.)

The ACLU lawyer wrote the school another letter, this time pointing out that my newsletter hadn’t come close to meeting the legal definition of obscenity (it would have had to be legitimately pornographic and also lack social, political, and artistic value). The school once again caved and retroactively reversed my suspension.

This would happen twice more my senior year, in November and December of 2002. The November suspension was for writing about how much I masturbate, and the December suspension was for an issue that ended with “fuck you, Mom.”

Like the first two, my third and fourth suspensions were both retroactively overturned and I graduated with a clean record.

Colorado State University

I attended Colorado State University in the spring of 2004 for one semester. I include this section only for completeness, as I wasn’t actioned by the school, but they did demand that I undergo a psychological evaluation if I ever sought readmittance.

During this time I repeatedly begged the opinion editor of the school paper, The Rocky Mountain Collegian to give me a column. Amused by my willingness to repeatedly enter the newspaper office and bother him at his desk, he relented and made me a guest columnist.

CSU’s athletic department had recently come under fire for hiring strippers for football recruitment parties, after which the strippers said they’d been sexually assaulted.

I wrote two columns about the situation before I was fired. The first was a milquetoast but sincere lament about sex work and the objectification of women.

The second was a satirical essay in which I proposed that CSU start a women’s bikini football league so I could ogle the players. I submitted the piece with the neutral title “Sexism in Sports,” but the humor-challenged editorial staff ran it with the confusing headline: “Sexism corrupts sports: Women score while men stare at them.”

Four students replied in letters to the editor—two commended my satire, and two called me a sexist pervert and urged the paper to fire me. They did, along with the opinion editor who’d hired me.

I then started a self-published newsletter that I handed out in my dorm called The Snowball. I wrote six issues, gained some fans and some haters (someone threw a chicken nugget at me once), and left the school at the end of the semester.

The University of Colorado

The Yeti

After brief stints in Los Angeles and Boston, I settled on the University of Colorado at Boulder as my school of choice. I was 21 when I started in the fall of 2006.

The Colorado Daily was an independent newspaper, not affiliated with the school, which had its office in the University Memorial Center (if CU were a high school, this would be the cafeteria).

They did not employ students and were not charmed by my repeated requests for a column.

There was a student paper, The Campus Press, but it was not widely read as The Colorado Daily overshadowed it.

I decided to self-publish a newsletter called The Yeti.

Issue #1 was about why girls don’t like me (because I’m too smart), and issue #2 was about why I’m afraid of black people. These got mixed but muted responses from the community.

Issue #3 caused a minor uproar. It was an essay about “the myth of the female orgasm.”

I was summoned to the office of vice chancellor Ronald Stump to discuss my essay. He framed the meeting as a warning, and asked me to stop distributing my newsletter, as it was upsetting people. Being well-versed in the First Amendment rights of public school students, I flatly refused.

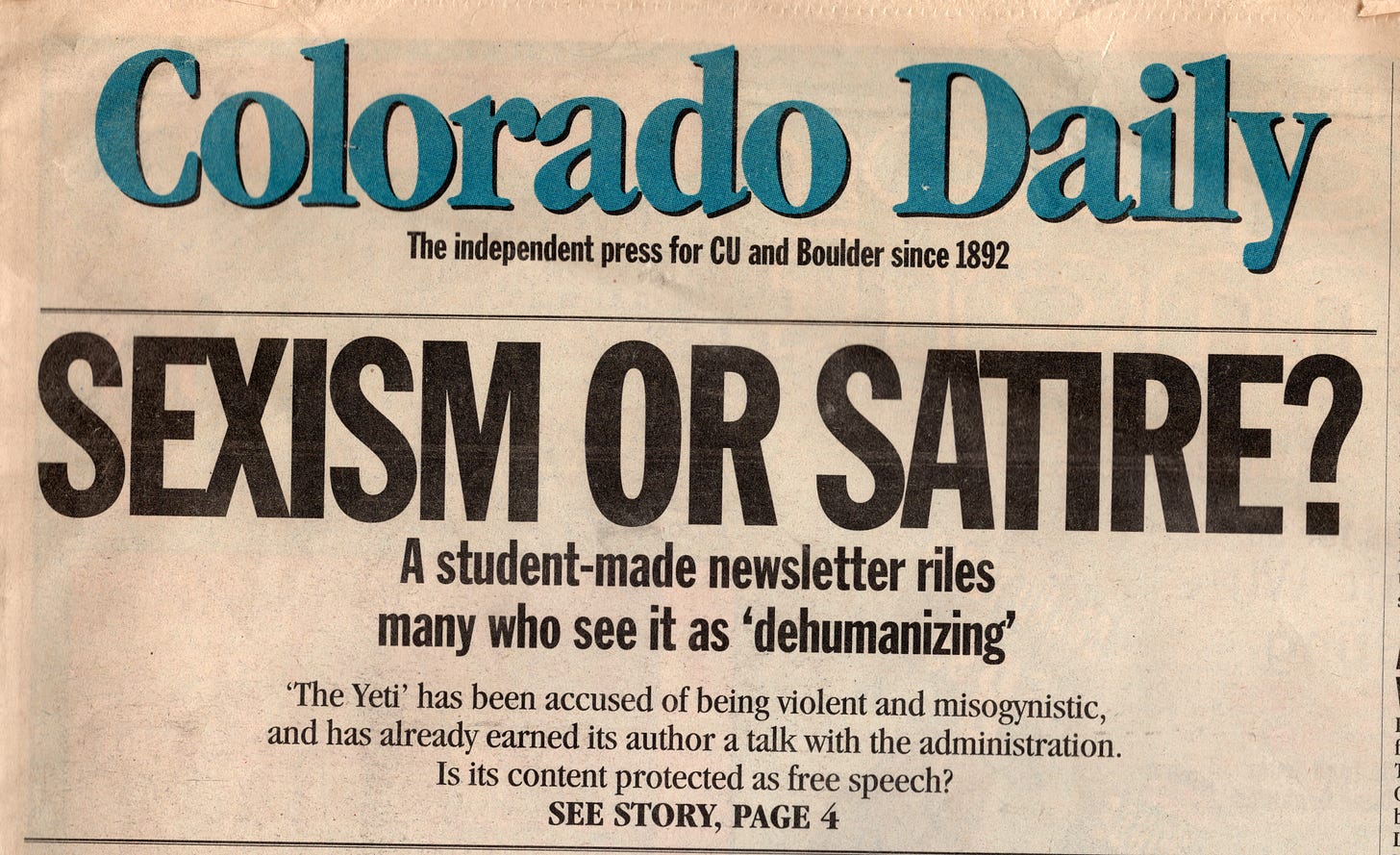

The Colorado Daily ran a story titled “Sexism or Satire?” detailing the community’s response to my piece, including the meeting with Stump. In response to the coverage, the ACLU wrote the school a letter warning Stump about his actions having a potential chilling effect on student speech.

The administration didn’t directly interfere with my newsletter again, but I’d made enemies of both Stump and the women’s studies department. On April 17, 2007, the day after the Virginia Tech shooting, they saw an opportunity to strike back.

The Virginia Tech Arrest

As part of a discussion in a class called Historical and Contemporary Issues of Black Women, our professor asked us for our reactions to the shooting. I was already working on a Yeti about the topic, and after hearing repeated claims of bewilderment and heartbreak from my classmates, I raised my hand and said, “Anyone who says they’ve never thought about shooting 32 people is lying.”

I went on to explain that, in a culture that celebrates violence and ignores the emotional problems of young people, it was irresponsible for us to play stupid: we’ve all been to public school, and it’s not a mystery why kids shoot each other.

Whether sincerely or not, my professor responded as though I may be making a threat to kill everyone, and asked for clarification. I clarified that I was not making a threat.

That afternoon, Ron Stump summoned me back to his office for a meeting where he suspended me for threatening my classmates. I asked him if he felt threatened by me, and he said, “No.”

When I left the meeting, there were two detectives waiting outside. One of them said, “I’m afraid it doesn’t end there, Max,” and held out a pair of handcuffs.

I was charged with “interference of faculty, staff, or students of an educational institution,” meaning that I’d made it impossible for the classroom to function normally by threatening to kill people. I spent the night in jail, and woke up to watch myself on CNN with the other inmates, who cheered.

I was barred from campus for the next two months, underwent regular drug and alcohol testing despite being straightedge, and a restraining order prevented me from coming within thirty feet of any of my ex-classmates.

I later found out that the police had been called not by my professor, but by the head of the women’s studies department. Upon hearing of my arrest, she cheered, “We got his ass.”

Four ACLU-affiliated lawyers represented me pro bono: two for the criminal charge, and two for my suspension from the school.

Both cases were resolved over the summer. After I refused to plead guilty (and after the media furor died down) the district attorney offered me deferred prosecution, meaning they’d drop the charges after one year if I didn’t commit any other crimes, which I accepted. The head of Judicial Affairs at CU was actually sympathetic to my story and retroactively reduced my suspension to three days, clearing me to return to class in the fall.

Here’s a video about the Virginia Tech arrest with more detail if you’re interested:

The Asians Article

The faculty advisor for The Campus Press was a fan of my work, and she asked me to join the school paper as an assistant opinion editor. I was astounded that, after everything, now I was being offered a job at a school paper, but I happily accepted.

The actual opinion editor was totally disinterested in her job, so I suggested that I read and edit all the submissions and then she could do a final review. She foolishly agreed, and just like that, I was somehow in command of the opinion section of CU’s student paper.

Each journalism student was required to submit an opinion piece as part of their curriculum, so I had a constant influx of material to work with. Some of them were weak writers, and I would give them notes and request that they make changes and resubmit their pieces, which everyone found annoying.

I didn’t get in trouble until a student sent me a moderately racist essay about how annoying it is that Latin Americans don’t speak better English. I edited the piece for grammar and submitted it to the editors.

At the next staff meeting, the editor-in-chief complained that the essay I was racist. I replied, “So what? The students are racist, and we’re the voice of the students, so the paper should be racist. We’re not here to make the student body look good, we’re here to amplify their voices.”

They found this argument compelling and we ran it. It’s actually still live on the new site.

Shortly after, I submitted an opinion piece of my own, titled “If it’s War the Asians Want, it’s War They’ll Get.” (This one is not still live on the new site, but here’s a copy if you’re interested.) It described my solution to the strained race relations between white and Asian students on campus: I was going to kidnap the Asians with butterfly nets and force them to Americanize.

My essay quickly became the most-read Campus Press article of all time, by a factor of about 100. The paper received hundreds of angry response submissions. My Facebook DMs were flooded with both fan mail and death threats. I personally got around 1000 emails over the course of a few days.

Everyone got fired. The entire paper was shut down and replaced by The CU Independent, which is structured so that it’s less directly affiliated with the school.

Dr. Phil’s staff reached out and invited me on the show to talk about my racist views. I wanted to go on and run circles around him. My lawyer explained that that’s now how it works when the host is in control of the audience. He said, “It’s a freak show, and you’re the freak.”

I wanted the exposure and the opportunity to grow my audience—the problem was I was realizing I didn’t have anything else to say. I was also realizing that the hate was taking a serious toll on me, and that I had other psychological issues I needed to work on in private. I decided to step away from public life for a decade or so.

Asian student groups, not understanding the satirical nature of the article, organized a giant protest against Asian hate. They sold shirts that said “in solidarity” on them. I attended the protest and surprised them by being friendly and wanting to take a picture together. We were, after all, on the same side.

Shame Lane

After college, I wrote an anonymous (at first) blog about my sexual development from birth. This was in 2010. I’m not sure blogger would host the same content today, given my blog’s focus on my childhood sexual experiences.

I’m now in the process of rewriting Shame Lane as a memoir.

Social Media Bans

YouTube

I started my YouTube channel, “mrgirl,” in the fall of 2017. Here’s an archived copy of the channel, hosted on Odysee.

My first video was a review of Mortal Kombat. My second was an essay about the Las Vegas shooting and violence in media.

I soon expanded into a wide variety of topics, using movie clips to illustrate my ideas while keeping myself off screen. After a year of hard work, and only 82 subscribers, it became clear that if I wanted any growth, I was going to have to become the face of the channel.

I decided I was as ready as I’ll ever be, and stepped back into public life. I made sure my face was in every thumbnail, and appeared on camera regularly.

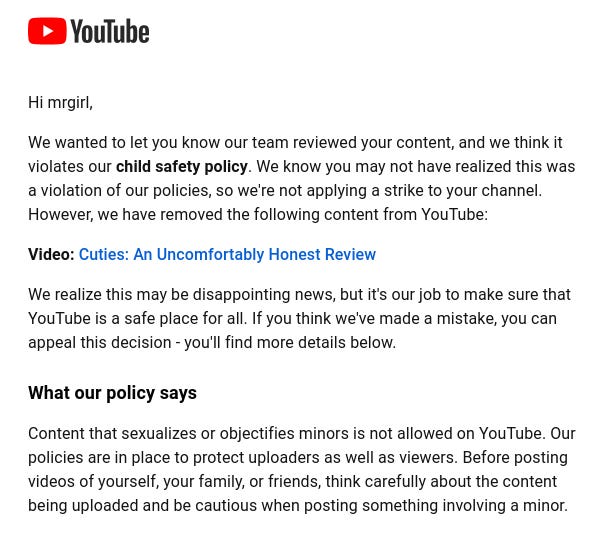

In September of 2020, I posted a review of the movie “Cuties” in which I said the film succeeded at making the eleven-year-old girls look hot.

Here’s the review, with the scenes of the girls dancing blurred out so I don’t get banned from Substack.

Within the next few days, dozens of content creators made videos about me calling me a pedophile. This is when I learned that “YouTube stupid” is on a whole different level from “college stupid.”

Here is penguinz0, also known as MoistCr1TiKaL, responding to my review.

The fans of these content creators, presumably mostly high school kids, flocked to my channel to leave negative comments and report my video. I received thousands of antisemitic death threats in the comments as well as emails and DMs. Probably 25% of the negative comments mentioned me being a Jew.

The comments also made excited predictions about when I would take the video down and private my accounts. Of course, I didn’t. I just kept making videos and ignored the backlash.

YouTube’s moderation system is a mysterious combination of automated and human decision-making, so I won’t pretend to know how or why any of this happened, but my Cuties review was removed and then quickly reinstated twice.

Both times, YouTube specified that I had not received a community guidelines strike (if you get three within 90 days, you get banned).

On December 19, 2020, my entire channel was banned.

My appeal was rejected two days later.

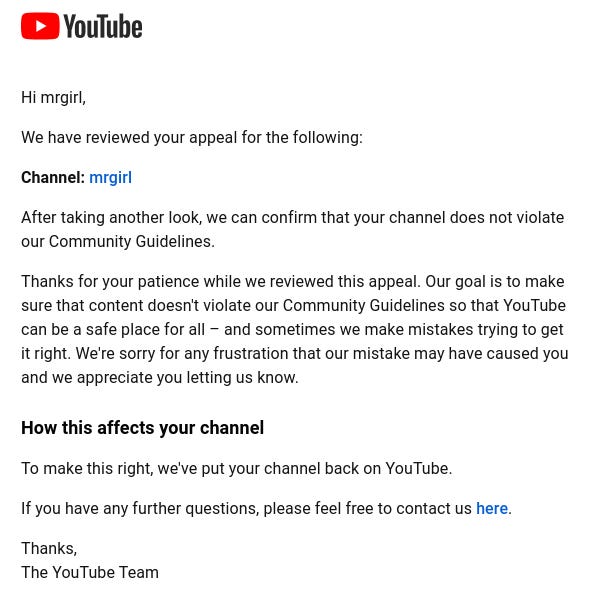

And then nearly four months later, I was unbanned. They even apologized for their mistake.

The Cuties review was also officially removed one last time, never to be reinstated. And as before, I didn’t receive a strike.

A few days later, I posted a parody of Eminem’s “Criminal.” Mine was called “I’m a Pedophile.”

Something I’d noticed about the criticisms of the Cuties review was that people thought I was totally unselfaware. This cleared that up, and a large chunk of my detractors became fans.

I was also getting compared to Weird Al, which I didn’t like, so I followed up with an original rap song called “I Can Fantasize About Whatever I Want.”

This song launched my modest rap career, and has garnered around 5 million streams on all platforms combined.

On June 22, 2021, I was banned again, this time for just two weeks.

This video, “I Made a PornHub Parody GIF,” was the culprit.

I started to understand that the moderators don’t actually watch your video when they ban you, so I could see how the title and some random screenshots could make you think it was porn. Also, since the Cuties review, my channel has been constantly reported by my detractors for anything that could possibly get me banned.

My third ban didn’t come until September 2022, following a series of debates with the livestreamer Destiny about his friendly relationship with the white supremacist Nick Fuentes. Fuentes called me out for obstructing his access to Destiny’s audience, and his own fans took it upon themselves to mass report my channel.

Both “I’m a Pedophile” and “I Can Fantasize About Whatever I Want” were removed for child safety, but the entire channel was ultimately banned for a video I’d posted in 2019 called “Why It’s Hard for Women to Say No.”

It was an anti-rape essay which used rape scenes from movies to illustrate my points. My ban was for nudity and sexual content.

What’s strange about this is that I’d received a strike for the same video back in 2020, and YouTube had actually accepted my appeal. Rather than remove the video, they age restricted it, and sent me this email specifying that it did not violate YouTube’s community guidelines

So it was pretty infuriating to later be banned entirely for the same video. If it broke the rules, why’d they put it back up in the first place when I appealed the strike in 2020?

I know asking this is futile, as it is unlikely the same people were involved in both decisions, if any humans were involved at all.

I appealed the channel ban several times, including on X, and was consistently rejected for several months.

In August 2023, nearly a year later, I appealed again and was reinstated.

I went through my channel’s backlog and took down anything that could possibly be construed as violating the nudity and sexual content policy.

Three weeks later, I was banned again, this time for violating the child safety policy.

Since no individual videos were removed, I have to assume it was because of the two music videos (which I’d posted back in 2021), but I actually have no idea.

All of my appeals have been rejected so far, and I’m still banned as of today.

TikTok

I posted “I Can Fantasize About Whatever I Want” on TikTok in the summer of 2021. It quickly exploded in popularity and I gained tens of thousands of followers in a matter of days. I was then mass reported and banned for child safety.

Twitch

I was banned on Twitch in March 2022, the day after I interviewed a woman in her early twenties who said she suffers from POCD—that is, obsessive compulsive thoughts about being a pedophile. I told her that she probably is a pedophile, but as long as she doesn’t act on it, so what? It’s not the end of the world.

This and my other content was reported to Twitch as being pro-pedophilia.

However, I never received any notification or email from Twitch, so I ultimately don’t know why I was banned.

Patreon

Patreon banned me in October 2023 with an email stating that they don’t allow the sexualization of minors. I don’t know what they were referring to, but my empathy for non-offending pedophiles is often misconstrued as me supporting child molestation (similarly to how my empathy for mass shooters was framed as me threatening to kill my classmates).

Last year I wrote an essay titled “People Shouldn’t Go to Jail For Looking at Child Pornography” in which I argued that, while child pornography should certainly be confiscated and destroyed, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to incarcerate lonely and desperate pedophiles for merely looking at it.

People Shouldn’t Go to Jail for Looking at Child Pornography

I enjoy masturbating to Cardi B music videos, cartoons about incest, and stories about men being sexually abused by their mothers on the website malesurvivor.org. I also used to watch real porn, but six months ago I stopped. I believe the financial incentives and pressures involved in porn make it so the performers can’t truly consent (I say this as someo…

Anyway, I wouldn’t be surprised if this essay played a part in Patreon’s decision to ban me.

My appeal was rejected and my request for clarification was ignored.

Apple Music and Genius

Apple Music removed “I Can Fantasize About Whatever I Want” from their service. I don’t know when or why.

Genius deleted my artist page and all the lyrics to my songs, though some of them have since been reuploaded.

Thoughts On Social Media Bans and Free Speech

I understand my work is provocative, and you may be thinking, “Well, what did you expect?”

I’m not particularly surprised by my bans, but it’s important that we not let cynicism undermine our right to express ourselves. Free speech in America is dying, and social media is the hole in the bottom of the boat.

When conservatives claim they’re being censored on social media, progressives like to gleefully point out that the First Amendment only protects our speech from government interference. That’s true, but it’s a problem, because modern social and political commentary is not shut down with fire hoses and pepper spray—you just get banned, and you never find out who banned you or why.

Even X, the supposed free speech platform (which has also banned and unbanned me three times), is clear in their terms of service that they will ban you if their “provisions of the Services to you is no longer commercially viable,” and that they may also ban you “for any other reason or no reason.”

Beyond shaping political and artistic expression via punitive measures, platforms wield the insidious power of the algorithm. There is no front page or shared reality on any social media site, so platforms can selectively suppress or promulgate whatever messages they want with no transparency.

When it feels like your political opponents are living in a different reality from you, it’s because they are.

In this incredibly polarized landscape, neither conservatives nor progressives believe in free speech. Conservatives are happy to ban pro-LGBT messaging, and progressives are happy to ban anything that meets their broad definition of bigotry. (And both are happy to ban satirical rap songs about being a pedophile.)

For me to continue to exist as an artist and social commentator, I’ll have to focus on mediums that don’t allow for the immediate back-and-forth with the audience that I’ve always loved. Spotify doesn’t have a “report the artist” button next to each of my songs, and my memoir sure as fuck won’t have one either. I should also note that Substack has been good to me so far.

But regardless of what happens to me, social media has become the de facto public square—the lunchroom of the internet. The public square shouldn’t be run like a cold, ruthless business.

Mrgirl complete victory

now that's a dick shin